The Law of the Land versus the Law of the Sea. at the Border of Maritime Ethics

Today, over 90 per cent of world trade travels by boat, and increasing societal and political attention is paid to the sea. The exploitation of maritime living and mineral resources attract interest and actors of all kinds, while tragic and controversial migrations – as people fleeing insecurity embark on perilous journeys to reach safety overseas – have turned the sea into a major geopolitical stage. In other words, more than ever before the sea has become central in shaping human life on dry land. Nevertheless, the sea remains often perceived and imagined as a space where only limited social life takes place, representing the unexperienced and unknown for those not living close to it. In reality, seawaters directly structure everyday life for a multitude of individuals, such as fishermen, sailors, seafarers, coastal communities, and islanders. For those living close to the sea and often earning a living from it, social life exists and is structured and constructed over and around the sea. Spending life on and at sea implies a specific understanding and experience of the interaction between dry land and the sea, and between humans out at sea. When the boundaries separating the safe dry land from the perilous seawater blur, a different formulation and understanding takes their place, adopting a ‘maritime way’.

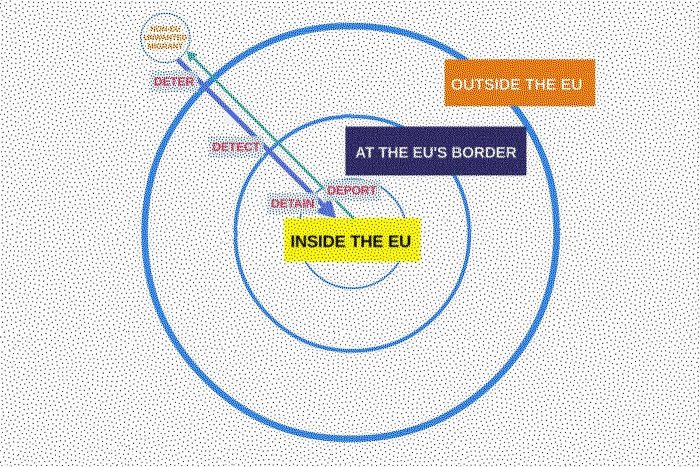

Graphic view of the EU integrated border management system

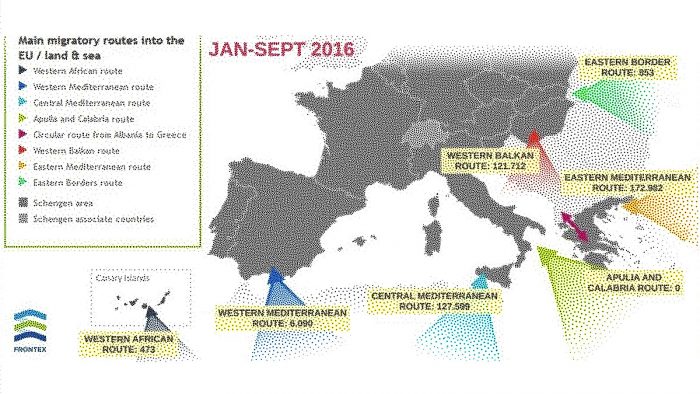

Frontex’s Migratory Routes Map page

An indicative line corresponding to the European external border. Google Earth image

With an increased number of human activities that have colonised the sea, a series of profound transformations have also mutated the ways in which the sea is experienced and perceived by coastal and maritime populations. In recent times, particularly controversial international borders started to alter maritime spaces in ways almost unseen before. Established to mark the social, political, economic and cultural spaces inhabited by specific populations, today extremely visible borders started to pop up in the seawaters surrounding affluent countries to separate them – both physically as well as symbolically – from ‘the rest’. While in previous decades the shores of Australia became the landing port for many South Asians undertaking extremely dangerous crossings to escape war, prosecution and poverty, for instance, since the end of the twentieth century the Mediterranean has turned into a mass graveyard for thousands of people seeking safety in Europe. With the media and politics almost obsessively producing and reproducing images of frequent death, rescues, and sufferance at sea, the everyday life of those living in the proximity of these seawaters has changed dramatically.

New policies, discourses and practices generated in country capitals started to almost forcibly structure life in isolated and peripheral coastal territories – often consisting of relatively small islands – and to affect their inhabitants. For locals, the perception and experience of that sea – which historically constituted a natural extension of social as well as geographical space, a bridge to reach the outside world, as well as the main source to gain a living – has changed dramatically. At the border, the encounter between the overlapping and yet separated worlds of the land and of the sea, produces tensions. An extreme actual example of these complex dynamics is certainly the one between Europe and the Mediterranean Sea. With the establishment of the Schengen space of free movement of people, a new and communitarian governance system started to regulate cross-border human mobility within Europe as well as outside of it. While internal national and linear borders were partly lifted so that European citizens could move freely across the EU, new mechanisms and apparatuses – border functions – started to operate, both outside and inside the EU. By contrast, ‘old’ national borders were reinforced – or militarised – when coinciding with the external boundaries of Europe: a line descending from Finland to Cyprus, then passing through Gibraltar, to then move down to reach and surround the Canary Islands.

With the official aim of controlling non-EU nationals’ unauthorised entrance and residence in the EU, a complex governance system was thus put into place to deter, detect, detain and deport ‘unwanted’ people. Working as a complex system of bottlenecks that operate already outside of Europe, those non-EU nationals escaping insecurity to enter the EU unlawfully were left with few options but to undertake perilous journeys at sea. Thousands of boat migrants started crossing Europe’s outer border, along limited stretches of it, to land in peripheral territories, such as the islands of Lampedusa, Lesbos and Fuerteventura. There, the institutional response became articulated into a series of joint military operations and the installation of security and surveillance devices to detect and rescue unauthorised people trying to cross.

Rescue operation from Lampedusa’s coast, 2011. Image from the Archivio Storico Lampedusa

Migrants at Lampedusa’s ferry quay, 2011. Image from the Archivio Storico Lampedusa

These activities, combined with unprecedented media and political attention, has changed the life of these islands and coastal communities as much as the individuals’ experience and perception of the sea. With many local fishermen frequently engaged in extremely costly rescue operations – both in financial and human terms – it is not just the local economy that is endangered. Since fishermen are forced to decide whether to save lives at sea, against the economic sustainability of their profession, it is the ethics of the sea that is in jeopardy. With migration being criminalised, depending on the nationalities of shipwrecked people, a series of legal risks increases the costs of helping them. Some of the most basic customary rule of the sea – namely to rescue anyone in need of help regardless of their passports – are compromised to sustain policies designed in European capitals that are often located hundreds of kilometres away from the seashore.

Yet, the frequent emergencies generated by the thousands of people coming in from the sea and forced to remain ‘at the border’ for months, further transform local socio-cultural fabrics. The hospitality typical of island and maritime communities is put to the test. For instance, in Lampedusa hospitality has historically characterised locals’ relation with those coming from the outside. Due to its geographical location, the island worked for centuries as a safe port for those navigating in the area, and it continues to do so. With locals experiencing isolation for the greater part of the year, islanders were used to arrange shelters and aid those in need at sea. Yet, today, on dry land as well as at sea, the ethics of the (people of the) sea are negated by the law of the land.

About the Author

With a focus on the most empirical outcomes of European integration, Giacomo Orsini has conducted much fieldwork research along the European external border in Melilla, Malta, Lampedusa and Fuerteventura. He is Senior Research Officer at the Department of Sociology of the University of Essex for the ESRC funded project ‘Bordering on Britishness: an Oral History Study of 20th century Gibraltar’. Since 2015 he has been working as Maître de Conference of the Institut d’Etudes Européennes of the Université Libre de Bruxelles. His research areas are concerned with borders, migration and asylum, maritime sociology and the sociology of everyday life, contemporary governance systems and governmentality.