Here But Not Here

I heard that about 500 Yemeni refugees entered Jeju Island in May. The news spread through the foreigner community network on Jeju first. Mostly English teachers from other countries, they jumped to help when there was not yet an NGO or a group of organized effort to help the refugees. There were so many people who needed help, and there were so many things to do in a very short time and without the time to organize the help. In the midst of the frenzied effort to help, Jeju people come forward to help. There was no heroic reason why they were helping. A family opened their home because they had an extra room. A woman cooked food for the refugees because she had been a stranger in a foreign place and could empathize. And many helped just because they could. I was one of them. We did what we could, but we weren’t ready for what came after. Yemeni refugees and volunteers were attacked and insulted with unspeakably hateful and purposefully menacing comments that spread very fast.

As an art therapist, I met Yemeni children to do art with them. But, soon, I found myself organizing Korean language classes, looking for housing for them, looking for employment for their fathers, looking for drivers, looking for money, and on and on. To make the matter even more hectic, I got phone calls all day long, non-stop. The callers asked me about the situation, about the structure, about the organization, and about who was doing what. I couldn’t answer because I didn’t have the perspective to see the outer structure of what I was in.

What I could fathom inside this chaos was not a structure or a pattern but the felt sense of vibrations from the other helpers. In the midst of not knowing how much we had to do, how far we had to go, and how long this was going to be, I felt the vibrations coming from other individuals who were trying to do something. We felt one another’s presence, and that was so assuring.

However, the voices of hatred and disgust spread at a lightning speed. At first, mothers, among others, said they were afraid to let their daughters out because these refugees, mostly young men, might sexually assault the girls. Then, later, the rumor had it that it really happened. Well, it didn’t happen. Actually, no crime was committed by Yemeni refugees in South Korea, but this fact didn’t stop spreading the rumor.

Historically, women have all the right reason to feel fear of sexual crimes. They happen all the time. Korean women have been taught by their mothers and sisters to feel afraid and to protect themselves by being careful, and we didn’t learn to fight or to do something with our anger. When an emotion is stuck inside, it wants to go out by finding a thing or a person to project itself on. And I think that’s what happened here.

There had been rape-murder cases that involve solo female tourists on the island, but that hadn’t deterred female tourists. The actual history of sexual crimes committed by American soldiers in South Korea hadn’t stopped the construction of the American naval base on this island, but these Yemeni refugees were categorized differently. They were darker colored, they are not like white people who are visible, or dark-colored migrant workers who are here but invisible. And they were escaping from a war when we didn’t want to be reminded of what it was like to be in a war. Fake news about the refugees spread like a virus, and people’s reaction was not that of hatred but that of disgust.

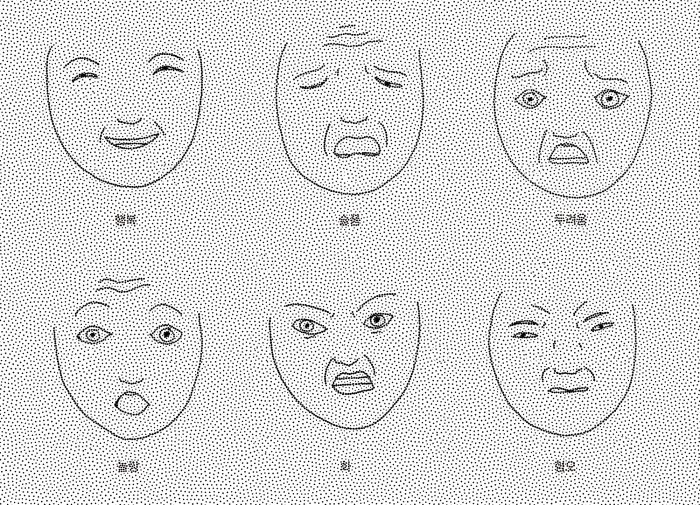

In the 1970s, the psychologist Paul Ekman discovered that facial expressions of the basic human emotions are not culturally determined but universal across human cultures and thus likely to be biological in origin. There are six basic emotions, and they are: happiness, sadness, fear, surprise, anger, and disgust. Even those who are born non-sighted make the same facial expressions. Of course, in our language and culture, there are many more emotions that we talk about, but it may not be an emotion, but a thought or a state in combination with cultural beliefs.

Fig. 1

The 6 basic emotions

Fig. 2

Drawings of the 6 emotions

When I do a workshop about the basic emotions, I ask people to make the facial expressions (Fig. 1) and then draw their emotions in colors and lines (Fig. 2). Some are easy to do (such as happiness and anger), some are a bit difficult (sadness and fear), and disgust is very difficult to draw. Just thinking and writing about it gives me a minor headache, and other people’s reactions are not that much different from mine when they are asked to draw and talk about their experience of disgust.

There are many theories and thoughts about human emotions, but there seems to be one indisputable truth: emotion comes and goes. An emotion disappears when it is left alone without suppressing it or distorting it to become something else. Meditators know this very well. Meditators train themselves to observe an emotion without labeling it or reacting to it so that it goes through its natural and organic course and disappears eventually. However, we have developed many methods to avoid, oppress, or project an emotion and thus extend it.

People ask me: Why is there only one positive emotion (happiness), and why are the rest of them negative emotions? This question puzzled me for a while, and then I realized that there were no good or bad emotions essentially. The reason that we have these emotions is not to make us happy but to help us survive. Each of these emotions helps us to respond in a way that’s appropriate to the circumstances that we find ourselves in.

For example, when we feel happy, our gaze softens, and we become less judgmental and more inclusive. When we feel fear, our senses sharpen. Our focus widens, and our senses of hearing and touch become more acute. And when we are angry, our gaze becomes laser-sharp at the person who has angered us, and the rest of the vision blurs. We only see the enemy in front of us, and our body quickly prepares us for the fight or flight mode.

What about disgust? It is thought that disgust is an emotional response of revulsion to something considered offensive or harmful. Evolutionarily, it is a response to protect the body from ingesting disease-carrying pathogens. Thus, the facial expression and the body language of the person who experiences disgust is like the person who wants to throw up.

South Korean people’s reaction to the Yemeni refugee was not that of hatred but that of disgust. And this came at a time when the expression of disgust referring to specific groups of people as “bugs” was becoming varied and being widely used. Even before Yemeni refugees came to this island, disgust existed within us throughout society, and I think it could mean that we lack the courage to face whatever that makes us feel angry and afraid. In such a situation, disgust acts like a self-defense mechanism. When we project or throw up, we don’t feel what is inside us.

South Korea has become one of the most economically successful countries in the world in the shortest time. This success has come with so many changes in the culture. For instance, the pattern in people’s relationships has changed dramatically. As South Korea has become wealthy, clean, and stable, people have lost tolerance for the entanglement and messiness found in close relationships. More and more young people choose to live alone, eat alone, play alone, and limit their relationships to a non-contact basis. In these individualized and almost hygienic relationships, instead of arguments and fights when there are problems in relationships, there are the severance of ties and lists of un-friends. And, at the societal level, when groups of people show wide gaps in opinions, they often attack one another with contempt and disgust.

Disgust spreads like a virus. And it affects those who fight against disgust, too. It was disgust I felt when I read hateful comments that I won’t repeat here. Instead of reporting the verbal abuses or dealing with them, I quickly deleted the comments from my SNS page because I could not bear seeing them for one more second.

I don’t think the way to stop spreading disgust is through love or through similar noble paths. Rather, I think we need to face what we are either afraid of or angry at already in our system first. Anger makes us approach, and fear makes us look for danger. By looking at them directly, we may be able to figure out what we have inside us that we are desperately trying to avoid. Perhaps fear teaches us to look carefully, and anger encourages us to go and face whatever we are trying to see.

Fig. 3

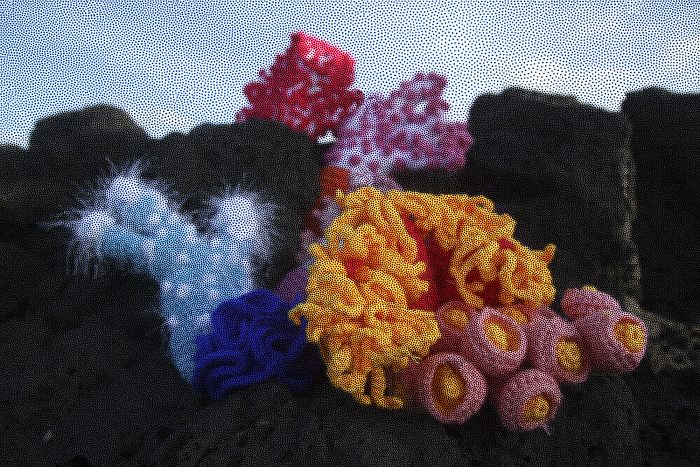

Jeju Soft Corals Crochet

Fig. 4

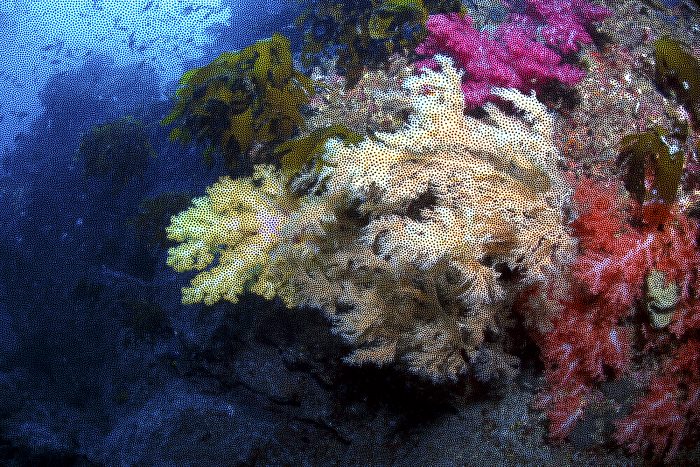

Jeju Soft Coral

I stopped volunteering because I was so fatigued. And, also, the Jeju Coral Crochet Project couldn’t wait any longer. Inspired by the international crochet coral reef project led by the Institute of Figuring (https://www.theiff.org) over the last 10 years, we began crocheting the beautiful soft corals that exist off the southern shore of Jeju island. The original coral crochet reef project involved thousands of women in a dozen countries. Using crocheting, which is the most effective method to create these curly structures, participants created free-form sculptures that resembled the colorful life forms in the ocean. Now, we are doing this project on this island because people don’t know that we have amazing soft coral Gardens and most people do not know that they are dying due to climate change and, more directly, the construction of a naval base in Gangjeong Village.

By “coral crochet,” we do not just mean crocheting corals. Rather, this is a term that we use to represent the fractal forms found in nature. Shorelines, cabbages, human brains, and corals, among many other things, have frilly and curly forms. They are so different from what we have built with straight lines and planes.

There is no straight line in the ocean. And there’s no separation here because all life forms are in direct contact with the water. The way of protecting oneself by separating and distancing does not work here. When I was relying on other people’s presence, which felt like the vibrations of separate dots, I thought how fragile this connection was. However, in the ocean, vibrations move far and wide, like the low-frequency sounds of a whale that travels many kilometers.

We invited Yemeni women to crochet with us. Using crocheting to visualize corals and the ocean, we wanted to envision a relationship that was tactically connected. My friends and I began this project with the intention to help people imagine corals and ocean life, but I wonder if we are looking for a way or an inspiration to save us while doing this project.

As we have cut our trees, forests, and mountains to make straight roads and straight buildings, we have totally changed the way we relate to other people. We are becoming more separated and lonely, and we see the “otherness” of other people as a sufficient reason to reject, to attach less-than-human labels, and to react in disgust. Although we are polluting the ocean and destroying the marine ecosystem and the entire ecology as the result, the ocean is still where the vibrations of all life forms are felt through the tactical medium of the water. Here, there is no way to claim that I am not connected with you.

About the Author

Jung Eunhae (born in 1972) is a painter, art therapist, and eco-art educator. She studied fine art at Queen’s University in Canada and art therapy at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. After spending her teen and young adult years in North America, first as an immigrant in Canada and then as an international student in the United States, she returned to South Korea and found home in a small village with a beautiful evergreen forest on Jeju Island. Now, she conducts nature workshops and implements various projects where community, ecology, healing, and arts intersect through the organization Jeju Eco Project OROT, which she founded with an environmental activist and a community organizer. Her publications include Don’t Be Afraid to Be Happy and Art Journal for Transformation and Growth.