Brexit, the Commonwealth,

and Exclusionary Citizenship

Many modern nation states have grappled with the issue of making migrants into citizens. Britain, conversely, has turned citizens into migrants. The latest episode was the referendum on 23 June 2016 that determined, by a slim majority, that the UK should leave the European Union.

Since then, there has been much debate and discussion on what Brexit should look like and how it should be organised. But one thing at least is very clear: that the rhetoric on migration, which intensified and inflamed the national discussion in the period leading up to the vote, is a red line not to be crossed. Whatever else may be up for discussion, ‘taking back control of our borders’ and ‘reclaiming sovereignty’ in order to do this are not. While the details are to be worked out, it is likely that Brexit will involve taking rights away from non-British EU citizens and turning them into migrants with limited rights to enter, live, and work in the UK. Simultaneously, British EU citizens will lose similar rights on the continent.

This is part of a broader pattern that played out in the first half of the twentieth century with regard to people coming to Britain from the Commonwealth.

The fluidity of British citizenship over time

Until the passing of the 1948 British Nationality Act (BNA), there had been no formal designation of citizenship within Britain or the British Empire at large. Instead, there was a general understanding that all those who were subject to British rule were British subjects. This had had few political consequences for those living in Britain at the height of empire. But during the period of decolonisation, and the voluntary movement of people to the metropole, this changed.

British citizenship, together with the right to live and work in Britain, was afforded to in excess of 850 million people in 1948.

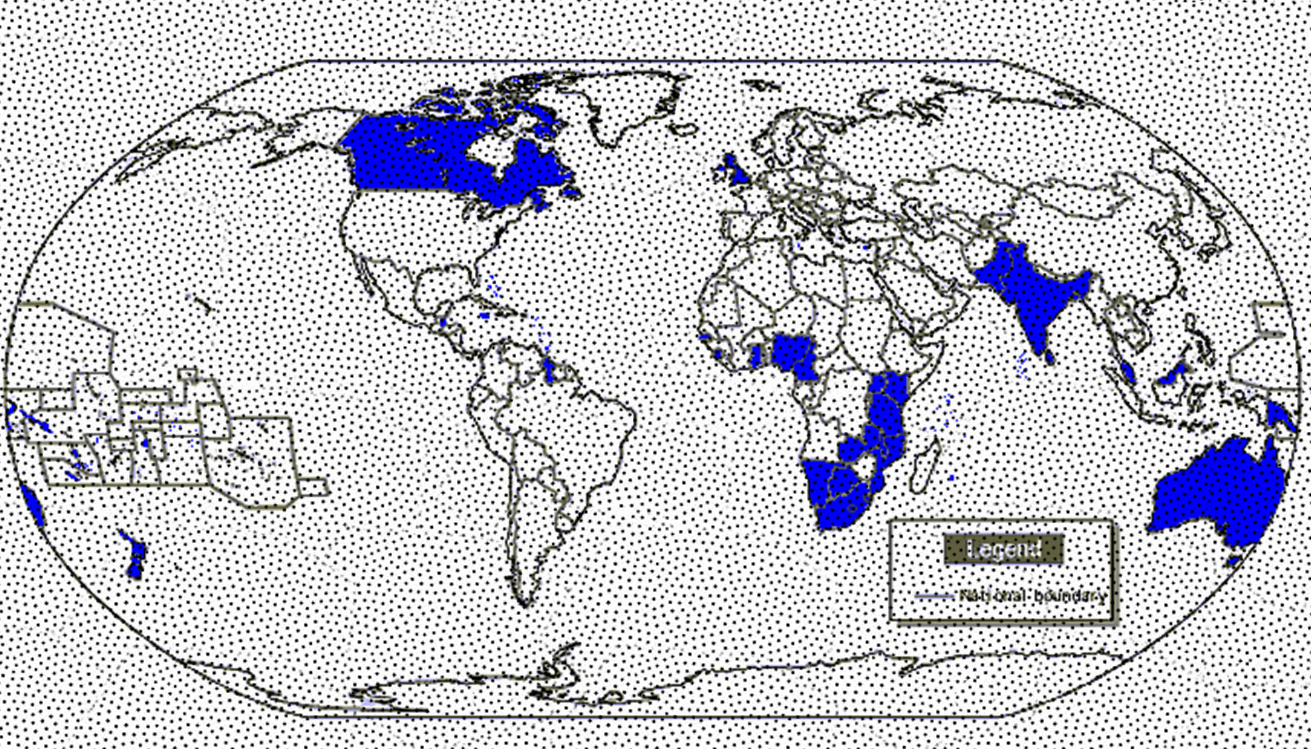

Fig. 1

Map of the Commonwealth of Nations (formerly the British Commonwealth). Member states are coloured blue.

The BNA was passed in light of India gaining her independence in 1947 and the white settler dominion colonies of Canada, New Zealand, and Australia set to become fully independent in 1948. As Britain was still an imperial state, despite these losses, the form of citizenship outlined in the BNA was shared across the UK, its colonies, its former colonies, and its dominion territories. These were ‘Citizen of the UK and its Colonies’ and ‘Commonwealth Citizen’ (all those from the former colonies and dominions such as India, Canada, Australia etc. were eligible); there was no separate or distinct category of citizenship for people in Britain. At the point of setting out the BNA in 1948, then, British citizenship, together with the right to live and work in Britain, was afforded to in excess of 850 million people (albeit within the white dominion whites-only immigration policies excluded fellow British subjects).

As the direction of movement in the preceding centuries had predominantly been from Britain to the rest of the world, or across colonial territories, there was little consideration of the fact that people might also move from the imperial periphery to the centre. Once it occurred, this movement precipitated a radical reconsideration of citizenship and migration, and who was and was not (or should and should not be) entitled to its rights and benefits. These were questions that were returned to periodically in the postwar period in light of the movement of peoples through the various circuits of empire.

Moral panic and the post-war need for labour

Fig. 2

RAF officials from the Colonial Office welcoming Jamaican immigrants disembarked from the Empire Windrush at Tilbury docks, England, June 22, 1948 – Getty Images.

The postwar period in Britain was marked by a significant skills and labour shortage and there was a concerted effort by the government to recruit foreign and Commonwealth labour. Perhaps the most iconic event of those years is the docking of the Empire Windrush at Tilbury Docks and the disembarkation of some 500 British citizens from the West Indies in London. From the very day of their arrival a moral panic ensued in the country, which was couched in terms of issues of integration and the potential drain on resources (housing, schools) they would precipitate. It was more likely, however, that these concerns were a consequence of them being darker citizens than any actual detrimental economic impact on the lives of their paler compatriots.

Having disenfranchised hundreds of millions of its citizens by 1971, Britain then opened up its borders to 250 million new European citizens with barely a discussion.

This movement of British citizens from the darker countries – as was their right, under the 1948 British Nationality Act – was thrown into relief by a much greater movement of people to Britain who didn’t have British citizenship, about whom very little was written then or is discussed now. In the five years after the end of the second world war, close on 100,000 Eastern European refugee workers from displaced persons camps in Italy, Germany and Austria were recruited directly to work in Britain. Those who passed the medical examination, Hywel Gordon Maslen writes, “were transported to Britain and allocated three years’ state-directed employment, accommodation, social welfare and education. They were then permitted to naturalise” (incidentally, European Jews were explicitly prohibited from the scheme). In addition, approximately 128,000 people of Polish origin (specifically, Polish armed forces in exile in Britain, along with their dependants) settled permanently in Britain under the terms of the Polish Resettlement Act, 1947.

Compared with the scale and intensity of European migration to Britain, the arrival of around 500 West Indian British citizens in 1948 should have been considered insignificant; especially as “they were Commonwealth citizens who were … entitled to reside in the United Kingdom with full access to citizenship rights and privileges”. Yet, the debates in parliament at the time, for example, were around the pressures placed on housing and schools by the darker British citizens. They did not mention any of the difficulties posed by the largely non-English speaking European migrants and workers. The expressed concerns regarding their presence were taken up by government and used to pursue policies seeking to limit their entry into the country.

As it was not possible to reform the British Nationality Act and directly reduce the scope of who was to be considered a citizen, citizenship was then to be circumscribed through the passing of increasingly restrictive Commonwealth Immigration Acts based on racialised understandings of belonging. It was in this way that citizens were turned into migrants in the 1960s and 1970s with the loss of rights and privileges that had previously been afforded to them.

The last Commonwealth Immigration Act was passed in 1971 and Britain joined the European Economic Community in 1973. Having disenfranchised hundreds of millions of its citizens through immigration control, Britain then opened up its borders to 250 million new European citizens with barely a line of discussion in parliament concerning this momentous event.

And around and around we go

Citizenship is a central element of modern nation states and citizens tend to be defined against migrants. How we understand the conceptual distinction between citizens and migrants contributes to the ways in which we organise politics in the present. Given that concepts are shaped by historical understandings, if those histories are inadequate then our concepts are also likely to be less effective or even detrimental. It is only by acknowledging the history of disenfranchisement that characterises the recent past of Britain that we can begin to understand the casualness with which 52% of the population voted in June to strip us all of rights that we have enjoyed for the last 43 years. It is not an unusual occurrence, but simply the latest episode.

Fig. 3

Front cover of British passport issued in 2002.

Further, while the election was formally about membership of the European Union and much of the hostility has been directed particularly at Eastern Europeans, this xenophobia rests on sedimented layers of racism and racist policy-making. The failure to recognise darker citizens as citizens is apparent in the calls to ‘go home’. “We voted Leave, why haven’t you left yet?” is a question that targets not just non-British Eastern European citizens, but also darker British citizens.

This confusion around citizenship is perpetuated within academic and media discourses. Darker citizens are routinely labelled as second generation migrants even if they and their families have held British citizenship for as long as it has been available. This is the landscape in which EU citizens themselves have routinely, and erroneously, been termed migrants instead of being recognised as fellow citizens.

This systematic misrecognition – conceptual more than individual – gives weight to the lie that Britain was ever a homogenous nation state. It fails to acknowledge that Britain has always been a constituent part of larger political units – empire, Commonwealth, the European Union. While Britain was certainly the dominant entity in the first and second, it could claim no such uncontested authority within the European Union. This has implications for how we understand citizenship.

This loss of dominance and the petulance with which Brexit is occurring indicates, perhaps, the final death throes of the British Empire. This is demonstrated clearly in the Brexiteers’ rhetoric about the Commonwealth (a euphemism for Empire) and their puzzlement that India, for example, won’t just give Britain what it demands (access to its markets without any reciprocal move by Britain on freedom of movement). It is also demonstrated in the call to resurrect Winston Churchill’s dream of CANZUK – a federation of the (white) English-speaking nations, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the UK. It is with this project, that the truth of the Commonwealth Immigration Acts is revealed, and the association of citizenship and race becomes clearly apparent.

About the Author

Gurminder K. Bhambra is Professor of Postcolonial and Decolonial Studies in the School of Global Studies, University of Sussex. Previously, she was Professor of Sociology at the University of Warwick and also Guest Professor of Sociology and History at the Centre for Concurrences in Colonial and Postcolonial Studies, Linnaeus University, Sweden (2016–18). In March 2017, she was Visiting Professor at EHESS, Paris; for the academic year 2014–15, she was Visiting Fellow in the Department of Sociology, Princeton University and Visitor at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. She has also held a Visiting Position at the Department of Sociology, University of Brasilia, Brazil and is affiliated with REMESO, Linköping University, Sweden. Her first monograph, Rethinking Modernity: Postcolonialism and the Sociological Imagination (Palgrave, 2007), won the 2008 Philip Abrams Memorial Prize for best first book in sociology. It addressed how, within sociological understandings of modernity, the experiences and claims of non-European ‘others’ have been rendered invisible to the standard narratives and analytical frameworks of sociology. In challenging the dominant, Eurocentred accounts of the emergence and development of modernity, she has put forward an argument for the recognition of ‘connected histories’ in the reconstruction of historical sociology at a global level. This argument for a global historical sociology can be found in her second book, Connected Sociologies (Bloomsbury, 2014), which is open access and free to read at this link.